“Rebuilding trust between Northeast Neighborhood residents and the City, repairing past harms, and reconnecting today’s Northeast Neighborhood to the heart of the city are our most important goals. We commit to prioritizing the needs, wants, and desires of Northeast Neighborhood community members as we scope potential future investments in the community.”

~ Harrisonburg Community Connectors Vision Statement

Harrisonburg was selected in September 2023 to be the recipient of a Community Connectors Program grant through national nonprofit Smart Growth America, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The grant of $130,000 was focused on building local capacity to co-design projects alongside impacted communities to advance new transportation infrastructure projects that repair damage from divisive infrastructure.

The Community Connectors team is led by the Northeast Neighborhood Association, Shenandoah Valley Black Heritage Project, Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance, Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority, and the City government.

The Harrisonburg Community Connectors Program included four components developed by the project team:

- The Northeast Neighborhood Small Area Plan

- The Complete Streets Leadership Academy and North Mason Complete Street Demonstration Project

- Urban Renewal Historical Research

- Facilitated Community Dialogues

Small Area Plan

The Harrisonburg Community Connectors project worked with Northeast Neighborhood community members to create a Small Area Plan to guide future growth and investment in the area. CHPlanning served as the planning consultant for the development of the Small Area Plan. The Northeast Neighborhood Small Area Plan is the City of Harrisonburg’s first for a neighborhood. This community-driven Small Area Plan recommends tangible actions to achieve the Northeast Neighborhood’s vision. The Small Area Plan was developed through numerous neighborhood listening sessions, a design charette, and a neighborhood survey. The Small Area Plan will provide the basis for future land use and transportation planning, urban design, investment decisions in capital projects and programs, and services, and changes to zoning laws. This plan will be appended to the Comprehensive Plan, and is intended to guide community leaders, residents, institutions, community-based organizations, City staff, property owners, and developers.

It is organized into six sections:

- Introduction: Provides an overview of the plan, including its purpose, key goals, and general planning overview.

- Acknowledging the Neighborhood’s Past: Discusses the Northeast Neighborhood's history, from its time as a prominent settlement for freedmen up to Urban Renewal and its impact.

- Understanding the Present: Reviews the current social, cultural, and geographic landscape of the Northeast Neighborhood, including community characteristics and demographic trends.

- Community Engagement: Provides an overview of the various engagement pathways undertaken by the project team for the plan. It highlights some key takeaways from the engagement process and a narrative of community feedback.

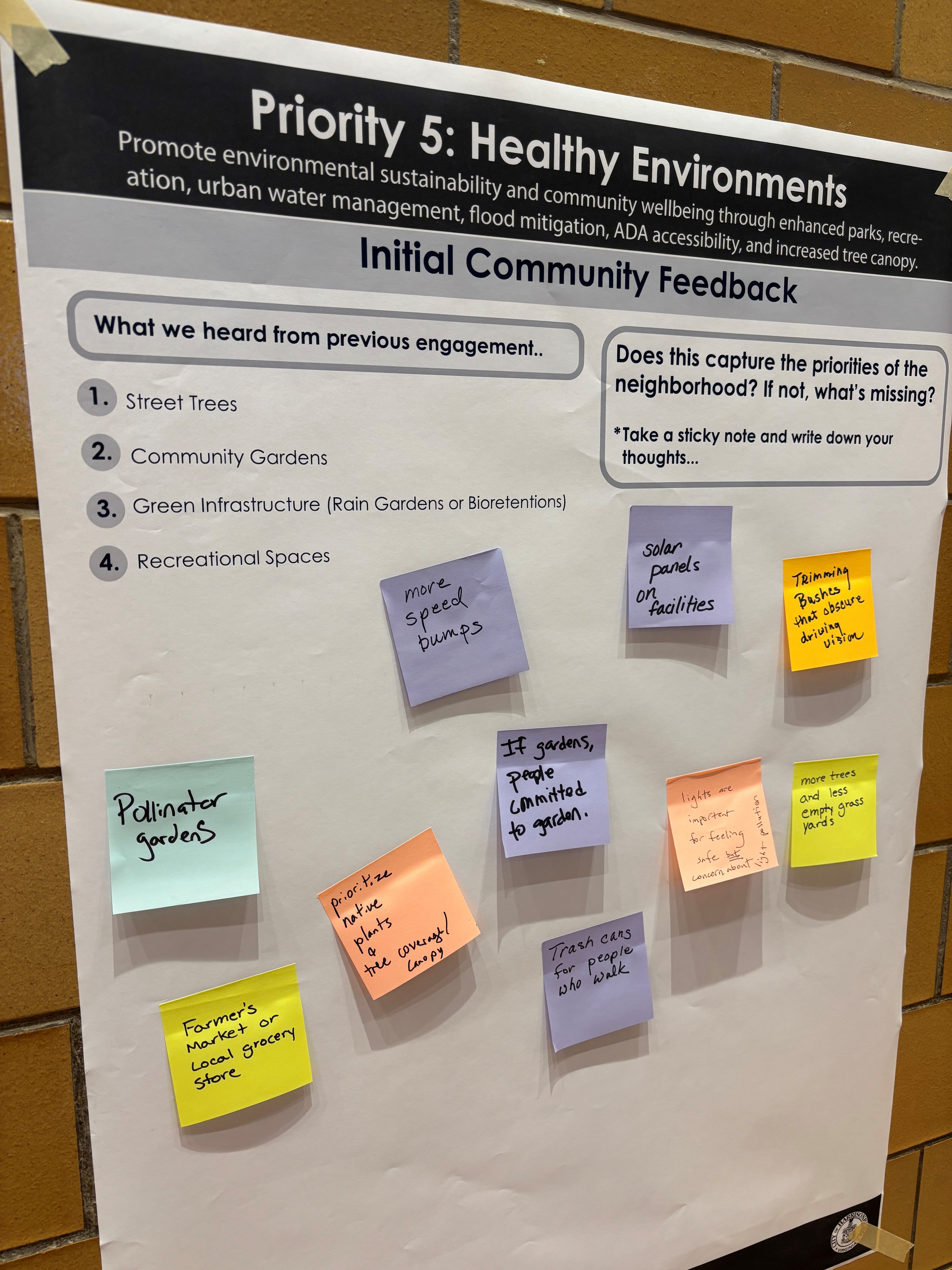

- Planning for the Future: Community Priorities, Goals, and Strategies: Synthesizes gathered information and feedback to produce targeted ideas for a shared vision of the future. The goals and strategies are organized under five key priorities: 1) Gathering and Belonging; 2) Reconnecting to Downtown; 3) Safety and Security; 4) Opportunity for All; and 5) Healthy Environments.

- Implementation Plan: Outlines actions for implementing the goals and strategies. The implementation plan is organized into a matrix that establishes a priority hierarchy based on public feedback. Each strategy includes responsible entities, key partners, and potential funding sources.

View the Small Area Plan [10.1MB]

View the PowerPoint Presentation of the Small Area Plan [3.6MB]

The Complete Streets Leadership Academy and North Mason Complete Street Demonstration Project

The N. Mason Street Complete Streets Demonstration Project was a product of the Community Connectors Program and the Complete Streets Leadership Academy. City staff, residents, and business owners of the Northeast Neighborhood collaboratively designed a road reconfiguration of N. Mason Street which was implemented as a demonstration project in July 2025. The Complete Streets demonstration project was grant funded through Smart Growth America and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The Complete Streets Leadership Academy is offered by Smart Growth America to communities across the United States. The Academy combines a series of virtual sessions and in-person workshops to develop and deploy community-led quick-build projects to test potential changes to streets; engage the community and solicit feedback in a more creative forum; and educate local city staff, advocates, and residents about transportation issues. The sessions and workshops cover the basics of quick-build projects including site selection, design, community engagement, and data collection, and how to use the experience to create long-term change. Participants design and deploy a quick-build project during the program and consider how to apply the lessons learned from the demonstration to inform future projects and the processes needed to support its development.

N. Mason Street Complete Streets Leadership Academy participants were:

- Matthew Bucher, Northeast Neighborhood Resident

- Kyle Lawrence, Northeast Neighborhood Resident

- Valerie Washington, Northeast Neighborhood Resident

- David Stuart, Northeast Neighborhood Business Owner

- Taya Whitley, Northeast Neighborhood Resident

- Charles Byrd Sr., Northeast Neighborhood Resident

- Karen Thomas, Northeast Neighborhood Association

- Monica Robinson, Shenandoah Valley Black Heritage Project

- Andrea Dono, Harrisonburg Downtown Renaissance

- Duane Bontrager, Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority

- Michael Parks, City of Harrisonburg

- Matthew Huston, City of Harrisonburg

- Nyrma Soffel, City of Harrisonburg

- Thanh Dang, City of Harrisonburg

- Tom Hartman, City of Harrisonburg

- Jakob zumFelde, City of Harrisonburg

- James Polhamus, City of Harrisonburg

- Tim Mason, City of Harrisonburg

- Amy Snider, City of Harrisonburg

- Lauren Nofsinger, City of Harrisonburg

Learn more about the North Mason Complete Street Demonstration Project.

Historical Research Efforts

The Harrisonburg Community Connectors project team hired a team to conduct additional research into the history of and impact of Urban Renewal on Harrisonburg residents and businesses. One of the major goals was to search for and identify any remaining Urban Renewal records generated by and in the possession of local repositories and public bodies, particularly the Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority (HRHA), which planned and implemented Harrisonburg’s two urban renewal and public housing projects.

The team searched for:

- Residential relocation records, property acquisition files, minutes, maps, plans, and any other HRHA documents related to urban renewal.

- Relevant City Council minutes along with documentation generated by or in the possession of City departments, particularly the Community Development (formerly Planning) Department.

- Deeds documenting the acquisition of urban renewal project land and sale of cleared redevelopment parcels.

View the full report issued in July 2025

View individual records reviewed by the historical research team

Upcoming Community Connectors Events & Information Sessions

- September 20, 2025 - Northeast Neighborhood Luncheon

Recent Community Connectors Events & Information Sessions

- June 22, 2024 - First Baptist Church Festival, 611 Broad Street

- August 6, 2024 - National Night Out in the Northeast Neighborhood

- September 14, 2024 - Harrisonburg Rockingham African American Festival

- November 9, 2024 - Community Connectors Luncheon at the Lucy F. Simms Continuing Education Center

- December 9, 2024 - Northeast Neighborhood Virtual Town Hall Meeting

- February 15, 2025 - Community Visioning Session at the Lucy Simms Continuing Education Center

- June 2, 2025 - Draft Small Area Plan Community Input Meeting at the Lucy Simms Continuing Education Center

- July 12, 2025 - North Mason Street Blocks Party, North Mason Street between Gay Street and Elizabeth Street

- July 21, 2025 - Northeast Neighborhood historical research findings presentation at the Lucy F. Simms Continuing Education Center

Contact Us!

If you have questions about this effort or how you can take part, please email us at Michael.Parks@Harrisonburgva.gov.

History Of The Northeast Neighborhood: From Newtown To Urban Renewal

Riverbank, an 18th-century Virginia Riverfront plantation, was built by Col. William Burbridge Yancey (1803-1858) on over 35 acres along the Shenandoah River. In the 1850 census, it states that Yancey owned 14 slaves. Birth records state that Ambrose and Reuben Dallard, mulatto twin brothers, were born on June 14, 1866, to father Ambrose and mother Harriet. They spent the first 33 years of their lives laboring on the Riverbank. Upon hearing of the impending signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Dallard brothers decided to escape and later return for their families. The mistress of the plantation aided the brothers because having them onsite was a constant reminder of the harsh realities of sexual exploitation on plantations. They fled to Anne Arundel County in Maryland and joined the Union Army. When the Civil War ended, they returned to Rockingham County, retrieved their families, and settled in the Lacey Spring area known as Little Africa, Athens, and eventually Zenda.

On September 9, 1869, William and Hannah Carpenter deeded a sizeable tract east of land Lacey Spring on Fridley Gap Road to John Watson, Henry Frazier, and Reuben Dallard, trustees for the Virginia Conference of the Church for the United Brethren in Christ, for $30, to build a church, burial ground, and schoolhouse. Jacob Long, a nearby landowner and postmaster, oversaw the construction of a one-room chapel that stood 20 feet by 30 feet with two windows on each side. In addition to volunteering his time and labor, many believe that Mr. Long paid for much of the construction out of his own pocket. This may explain why grateful residents later referred to the new house of worship as “Long’s Chapel.” Henry Carter, Milton Grant, William Timbers, and Richard Fortune became the first freedmen to settle in the community. In 1882, Rockingham County built the “Athens School” in Zenda in order to provide additional space for the growing community. Unfortunately, a decline in population forced the school to close its doors in 1925. The remaining residents were then forced to travel south to Harrisonburg in order to attend the all-black Effinger Street School. By the turn of the century, Zenda had grown into a vibrant community with over 80 residents, a post office, a schoolhouse, a chapel, and a cemetery.

In 1869, months after purchasing land in Zenda, Ambrose Dallard purchased lots in the Crismon settlement in Rockingham County. The Rockingham County deed book states he made a $50 deposit with a promise to make two additional payments in October 1870 and 1871. Ambrose Dallard paid in full on October 27, 1870. Meanwhile, Reuben Dallard and William Johnson moved to Harrisonburg in the same year. Johnson had been enslaved in Madison County and sold to the Yancey’s at Riverbank. Having lived together for years, Johnson and Dallard formed a formidable friendship.

Best friends married sisters Amanda and Harriet. Reuben Dallard purchased for $80 lot 57 and ½ of lot 58 in the Jacob A. Zirkle addition in Harrisonburg, which became known as Newtown. Dallard paid a $40 deposit and promised to pay the remainder of the purchase price in 3 installments on Sept 18th of 1870, 1871, and 1872. Dallard paid the remaining balance full in 1871. Johnson and his sons purchased property on Johnson Street and built homes. The former enslaved men had defied all stereotypes and had become landowners, signifying success. Newtown was annexed by the City of Harrisonburg around 1892.

The Housing Act of 1949, a pivotal moment in the history of urban development, also known as the Taft-Ellender-Wagner Act, provided federal loans to cities like Harrisonburg to acquire and clear slum areas. These areas were then sold to private developers for redevelopment in accordance with a plan prepared by the city. The act also granted funds to cover two-thirds of the city’s costs in excess of the sale prices received from the developers and provided millions of dollars to create public housing throughout the country. In the 1950s, Harrisonburg, like many other cities, embarked on a mission to eradicate and replace the old with the new, leading to a better tomorrow for the nation’s cities. Advertisements for a better tomorrow were littered with promises of green spaces, rooftop gardens, and removing boundaries between interior and exterior spaces. This led to the ‘The City with the Planned Future’ slogan. The city’s leaders, including Mayor Lawrence Loewner and Mayor Frank Switzer, played key roles in this transformation, securing significant aid for two extensive city projects.

The “Harrisonburg Northeast Urban Renewal Project R-4,” as it was formally referred to in city documents, and its smaller tag-on, Project R-16, changed the fabric of the city’s Black community. The Harrisonburg Redevelopment and Housing Authority (HRHA), which now owns and operates more than 250 subsidized and income-restricted rental units and administers the housing choice voucher (“Section 8”) program, was initially established in 1955 in order to execute the project. Project R-4 intended to address the acute housing crisis by removing blighted housing in the Newtown area. The positive results were claimed to be increased tax revenue, new commercial development, and blighted housing replaced with new low-income housing. Project R-16 was intended to address the vision of a future dependent on automobile travel, parking needs, and the need for a transit-type facility. The positive results were claimed to address the need to revitalize the downtown business district and provide more accessibility to automobiles with modernized widened streets and expanded parking, which would attract shoppers to downtown. The Urban Renewal concept evolved alongside the Interstate 81 Cloverleaf design projects. The Interstate project was designed to usher travelers easily into a community for economic purposes and quickly return them to their travels.

The razing of homes in downtown and the creation of the Mason Street corridor pushed many residents further into the northeast section of the city. Caught up in this effort were homeowners who had worked and struggled to pay off a mortgage in order to own something to pass on to their children. These homes could never be described as blighted or slums. These were the homes with the manicured lawns, well-tended flowers and in some cases wrap around porches. Also destroyed were a number of black-owned businesses, including the Colonnade, which had a dance hall, restaurant, barbershop and poolroom.

Projects R-4 and R-16 resulted in the displacement of 166 families from downtown Harrisonburg. These traumatic events led to a lack of trust in government officials and the Mason Street corridor became a visible and mental separation of the Northeast community from the downtown area. Project R-4 and R-16 created streets and intersections not conducive to safe and convenient travel, and disconnected the Northeast Neighborhood from the center of Harrisonburg.